Human Being Journal

This is an archive of an article in Human Being Journal #5.

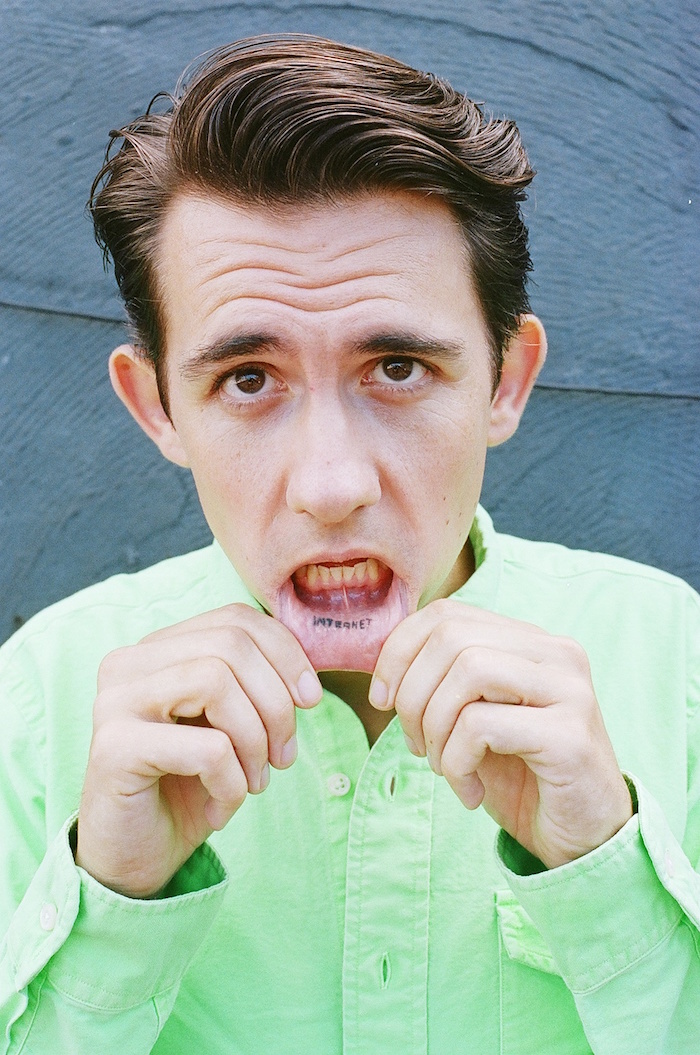

Text by Tag Christof, Photography by Clement Pascal.

In the early 1980s, Sherrie Levine gained notoriety for her groundbreaking exhibition After Walker Evans. She had photographed a number of the FSA master’s Great Depression-era photographs (notably all taken before she was born in 1947) and then hung and presented them, in all seriousness, as her original work. She had shot and developed the actual photos on display, so in a strictly ontological sense, the work was hers. But unlike earlier appropriation work, Levine made no attempt to disguise or alter the source. Instead, she made a game of subverting originality by calling it out in the exhibition’s title. The art world bristled. Was it still life? Was it original? Was it just shameless, lazy theft? And what did any of this mean for the value of a photograph as a piece of art?

Fast forward a few decades and art history has sided squarely with Levine. But the work of a new generation of digital artists is begging a similar set of questions around reproducibility, value and ownership. Rafae?l Rozendaal is among their foremost pioneers, having worked on the web prolifically since around the turn of the millennium. He trained as a conventional artist, but since 2001 has been buying up clever domain names on which to set up interactive artworks. The sites are singular — each contains one engaging scenario rendered in bright and proudly RGB palettes, and invites the user into a bit of unexpected usability. Among them are whitetrash.nl, pleasetouchme. com, hotdoom.com, beefchickenpork.com and several others.

To see Rozendaal’s work for the first time is a revelation, firstly because it occupies a generally humdrum, utilitarian space: the browser window you might spend several hours a day staring into. Secondly, because every piece is immediately intuitive and highly addictive—like a good arcade game. They all share a framework—on screen, in browser, interacted with through your device’s touch/keyboard/mouse interface—but each has its own physics and premise, and thus invites fresh consideration. They are both painting and installation.

Like Levine, Rozendaal has worked out an interesting multiplicity for his works. He sells them — he participated in last year’s inaugural PADDLES ON! auction, for instance—at which point the owner’s name appears in the title bar of the browser. Yet even when sold, the pieces continue to be freely available, accessible to all. When the norm for so long has been to buy art, pack it into a crate, move it expensively, and place it in a collection amongst other pieces, this phase shift is a Levine-like art historical moment with even bigger implications. Can art really live only on a screen? Why should anyone bother owning it at all?

But since, in the words of the organizers of PADDLES ON!, there is an “increasing viability of this (digital) work in the contemporary art marketplace,” those questions are pretty much moot. Because (financial) “viability” and (artistic) “legitimacy” are covertly interchangeable terms in the art market (one serving as a sort of a cheerful euphemism for the other), the fact that digital art now sells means that it has achieved legitimacy. More bluntly, enterprising gallerists and institutions have figured out how to monetize it, so of course it is real art. (Meanwhile, Jeff Koons continues to play multimillion dollar jokes on the art world yet few question their legitimacy.) At the end of the day, whatever the connotations of legitimacy and viability, it is good to see traditional doors blown open to hardworking artists like Rozendaal, so that they might pay the bills and continue to make brilliant work.

Aside from the websites, he started Bring Your Own Beamer (“beamer” being European for “video projector”), an event which invites digital artists of all sorts to gather and project their work in tandem. It makes for a vibrant and immersive experience, and in the spirit of the web, it has been opened to all participants, and regular BYOB events have been sprouting up all over the planet. At just over 30, Rozendaal has published books, lectured at lofty institutions like Yale and the E?cole des Beaux Arts, and has exhibited at the Centre Pompidou, the Stedelijk, TSCA Gallery Tokyo and many others. Market viable or not (and he is), Rozendaal is just about as legit as they come.

How did you come to focus your practice on digital art?

it’s fun

it’s new it’s light it’s open it’s cheap it’s free it’s everything it’s always it’s everywhere

no history no stress no boss no budget no deadlines no hassle

What sort of system do you work on?

My system… oscillating between pressure and void, between focus and numbness. Long periods of doing nothing, mixed with short bursts of sitting down and sketching, until I find an idea. Finding the idea is most of the work, though it’s hard to call it work. Once the idea is there, usually it starts as a simple sketch… then I work on the computer, I try different options. I love that the computer makes it so easy to make many variations of an idea. Once I’m happy with the direction, I send the computer sketch to my programmer and I explain what kind of motion/interaction I have in mind. I might make a rough animation, and he will work on a prototype. I can change values in that prototype, so the behavior/feeling of the work can be adjusted. Once I’m happy, I choose a domain name and the website goes live.

Or did you literally mean what kind of OS/software?

Yes! That’s all fascinating, but yes, what kind of OS/software?

Macbook Pro Retina 13″ with Thunderbolt display 27″ Audioengine speakers

iPhone

OP-1 for making melodies/sounds

Kindle Paperwhite for reading

Software: Adobe Illustrator mostly… that’s really my favorite for exploring and finding a form.

I use Fabriano sketchbooks and Uniball Vision Elite pens.

That’s my setup. My programmer has a different setup, Windows/Android, using mostly opensource coding environments. It’s great that we’re on different platforms so we can test the work in both systems.

You’ve participated in events like the PADDLES ON! auction, and a lot is being made of the newfound viability of digital art in the marketplace. Has this new “legitimacy” changed anything about your practice?

I’ve been selling more, which is great. The growing demand for my work made it possible for me to move to New York. Now that I live here, I seem to work faster. Even though the city is exhausting, it gives you energy. It’s very funny how that works… I try not to think about the legitimacy of the work, because it is so relative and subjective, there is never an answer. I accepted that as an artist you will never know where your work stands, you have to be comfortable with the uncertain. I’m very grateful that I get to do what I want every day.

Devil’s advocate question: what’s the point of ownership when everyone has access to your work at all times?

(Or is that the point?)

If you are a collector who wants to share a vision, it makes a lot of sense. Think of museums—they own work that is publically accessible. Art should be visible as much as possible

so we can all learn from it. I think serious collectors want to build a serious collection and eventually share their vision. Buying a website speeds up the sharing of that vision.

Has anyone ever appropriated your work in a way you weren’t happy with? How do you feel about copyright laws?

I think personal use is cool, but when a company profits from my work, I will approach them. It happened a few times, some companies had used my work in TV ads. We settled so it worked out OK.

Why is interactivity such an important element of your work?

I think interactivity is a big part of how we explore the world. When you are born, you are developing your senses. Touching is as big a part of discovery as seeing or hearing. It’s exciting that we now have the tools to work with interaction in an image. The user can influence the image.

It seemed natural to me to explore this. Interaction and interactive depiction has been researched in software and games, but it’s always a means to an end. You click a folder to open it, you shoot a gun to kill the bad guy.

I’m interested in interaction for the sake of interaction. I think we all love clicking.

Have you always had such a cheeky sense of humor?

I think I was much funnier when I was younger. I became more serious. There’s still some humor left…

What do you think will be left of the traditional art market in 100 years?

Art has been around for many centuries… millennia… but look at what happened the last 100 years. The art market continued, but cinema, TV, video games, recorded music and now internet, they are all new distributions of culture. I don’t make distinctions between “culture” and “art”, so I’d argue that the art market already changed a lot. There is the “fine art market” which will continue to exist, and there will be streaming culture, ideas that live on the network, whether it’s a TV show or a novel or a song. I’m always in favor of culture that is broadly accessible.